Is Your Privacy Secure When Taking Paid Surveys?

#1 Easiest Way to Get Free Amazon Gift Card Codes

July 14, 2021

The 7 Worst Mistakes Paid Surveys Rookies Make

September 18, 2021Is Your Privacy Secure When Taking Paid Surveys?

Hi, dear reader.

If you are a fan of paid surveys online, I’m sure you sometimes wonder if your privacy or personal data is safe.

With all the data breaches and hacking, we must be careful about what information we share online.

Taking paid surveys is a quick and easy way to make some extra money without much effort, but there are risks involved with

taking them.

This post will cover critical aspects like How Survey panels use cookies and personal data protection laws in different states.

Also, we give you solutions to keep your privacy safe.

Let’s get started

The Importance of Privacy in Paid Surveys

Privacy has become a rare and precious commodity in today’s digital age.

From online shopping to social media posts, our personal information is constantly being collected and analyzed by companies.

This is why it is essential to prioritize privacy when participating in paid surveys.

While taking surveys may seem harmless, our data can be used for various purposes.

Companies often sell survey responses to marketers eager to target specific demographics.

Inadvertently sharing sensitive information or personal preferences in these surveys could lead to targeted advertising or potential

privacy breaches.

Survey takers must understand how their data will be used and ensure their information remains secure.

Paid surveys seem like an innocent way to earn extra cash or rewards.

Still, they can only threaten our personal information with proper attention to privacy protocols.

It is vital for individuals interested in participating in these studies to research the survey provider’s reputation and clarify how

their data will be protected before sharing any personal details.

By taking active steps towards safeguarding our privacy while engaging in paid surveys, we can ensure that we make informed

decisions about our online activities and preserve our rights in this ever-connected world.

How Surveys Collect and Use Your Data

Surveys have become integral to market research, providing valuable insights into consumer preferences and behavior.

But have you ever wondered what happens to the data you provide when taking these surveys?

Surprisingly, many people need to know how survey platforms collect, store, and use their personal information.

When you participate in a survey, you may be asked to provide personal details such as age, gender, income level, or address.

While most reputable survey platforms claim to prioritize user privacy and data protection, it’s essential to understand that your

information isn’t always kept solely for research purposes.

Some survey companies may sell this data to third parties for marketing or advertising purposes.

This means that the information you freely provide could end up being used to target you with unwanted ads or even sold to

companies that specialize in identity theft.

Paying attention to the terms and conditions when participating in paid surveys is crucial, as they often outline how your data may

be shared or kept within the organization. Some companies claim anonymity but reserve the right to match your responses with

other data they possess about you from various sources.

This merging of datasets can result in a detailed profile being created without your explicit consent.

Risks and Vulnerabilities in Survey Data Storage

Data storage is a critical aspect of online surveys that must be considered when maintaining privacy and security.

While companies take measures to protect survey data, risks, and vulnerabilities still need attention.

- One primary risk is the potential for hackers or other malicious individuals’ unauthorized access to survey data.

- With valuable information on participants’ demographics, preferences, and even financial details in some cases, survey databases

- can be attractive targets for cybercriminals.

- Companies must implement robust encryption protocols and regularly update their security measures to mitigate these risks.

- Another vulnerability lies in the presence of third-party vendors who handle data storage for survey platforms.

- Companies often outsource their data management tasks to such vendors, which introduces an additional level of risk.

- It’s essential for organizations to thoroughly vet these vendors and ensure they have robust security practices in place.

- Furthermore, contractual agreements should explicitly address any liability issues related to breaches or mishandling of survey data.

Overall, while organizations try to store survey data securely, companies and participants must remain vigilant about potential

risks and vulnerabilities to address them and protect privacy.

Steps to Protect Your Privacy When Taking Surveys

When taking surveys online, protecting your privacy should be a top priority.

While paid surveys can be a great way to earn some extra money, it’s important to remember that you are providing personal

information in exchange for this opportunity.

To ensure your privacy remains secure, follow these simple steps:

- First and foremost, never provide any sensitive information, such as your Social Security number or bank account details, when participating in a survey. Legitimate survey companies do not require this information, and asking for it should immediately raise red flags.

- Secondly, always read the privacy policy before agreeing to take a survey. This will give you an idea of how your data will be used and shared.

- Consider using a separate email address specifically for surveys to avoid cluttering your primary inbox with potential spam or unwanted marketing emails.

By following these steps, you can protect your privacy while still enjoying the benefits of taking paid surveys online.

The Role of Privacy Policies in Survey Platforms

Privacy policies play a crucial role in survey platforms by providing transparency and reassurance for users.

These policies outline how the platform collects, stores, and protects user data, ensuring participants’ personal information is

secure.

By clearly stating their privacy practices, survey platforms can build trust with their users and encourage participation.

In addition to safeguarding personal information, privacy policies outline the purpose of data collection and use.

This allows participants to make informed decisions about sharing their knowledge and ensures that their data is utilized

consistently with their expectations.

Privacy policies may also provide options for users to control the use of their data, such as opting out of certain types of research

or choosing what personal details are shared in surveys.

Survey platforms prioritizing privacy often go beyond legal requirements to implement additional security measures.

This could include encrypting user data during transmission or storage, regularly auditing their systems for vulnerabilities, or

partnering with trusted third-party vendors who adhere to stringent privacy standards.

These platforms demonstrate a commitment to protecting user confidentiality by going above and beyond minimum

requirements.

Overall, privacy policies are essential to survey platforms as they clarify how user data is handled while instilling confidence

among participants. Implementing transparent privacy practices helps protect sensitive information.

It enables individuals to make informed choices about survey participation without compromising their digital security.

What a cookie is.

Cookies are essential to the modern Internet.

HTTP cookies help web developers give you more personal, convenient website visits as a necessary part of web browsing.

Cookies let websites remember you, your website logins, shopping carts, and more.Â

Cookies are text files with some data like a username and password to identify your computer as you use a computer network and improve your web

browsing experience.

Data stored in a cookie comes with a unique ID for you and your computer.

When the cookie goes between your computer and the network server, the server reads the ID and knows what information to serve you

specifically.

A cookie cannot contain any virus or damage your device.

Some cookies are strictly necessary for an optimum operation of a website.

Others have different functionalities, like favoring the navigation between sites, allowing a site to remember your preferences, or detecting if you have

visited the site previously.

By their origin, cookies can be:

- First-party cookies:Â It is the visited site the one setting them.

- Third-party cookies:Â Cookies set by a server from another domain, although always with the authorization of the visited site.

All internet users can freely choose whether to authorize a site to drop ‘cookies’ on their device.

One way to do this is through the web browser’s settings, and the user can delete all the already dipped cookies and choose whether to accept them.

Source Kaspersky (What are Cookies?)Â

How do Survey Panels use Cookies?

All survey panels and market research business uses cookies because they are indispensable for adequately working for the panel and tracking

completed studies.

At IOpenUSA, use the Cint Cookie Policy(https://www.cint.com/cookie-usage) >We use cookies to verify that you have completed a survey.

We may also use cookies to track what websites (in addition to survey sites) you visit, regardless of whether such websites belong to us or a third

party, and what campaigns and other online advertising you attend.

Also, We use both session cookies and persistent cookies.

- Â A persistent cookie consists of a text file sent by a web server to a web browser, which will be stored by the browser and will remain valid until its set expiry date (unless deleted by the user before the expiry date)

- A session cookie, on the other hand, will expire at the end of the user session when the web browser is closed.Â

Also, Read > How to Become a Paid Surveys Influencer.

How Protected is Your Privacy?

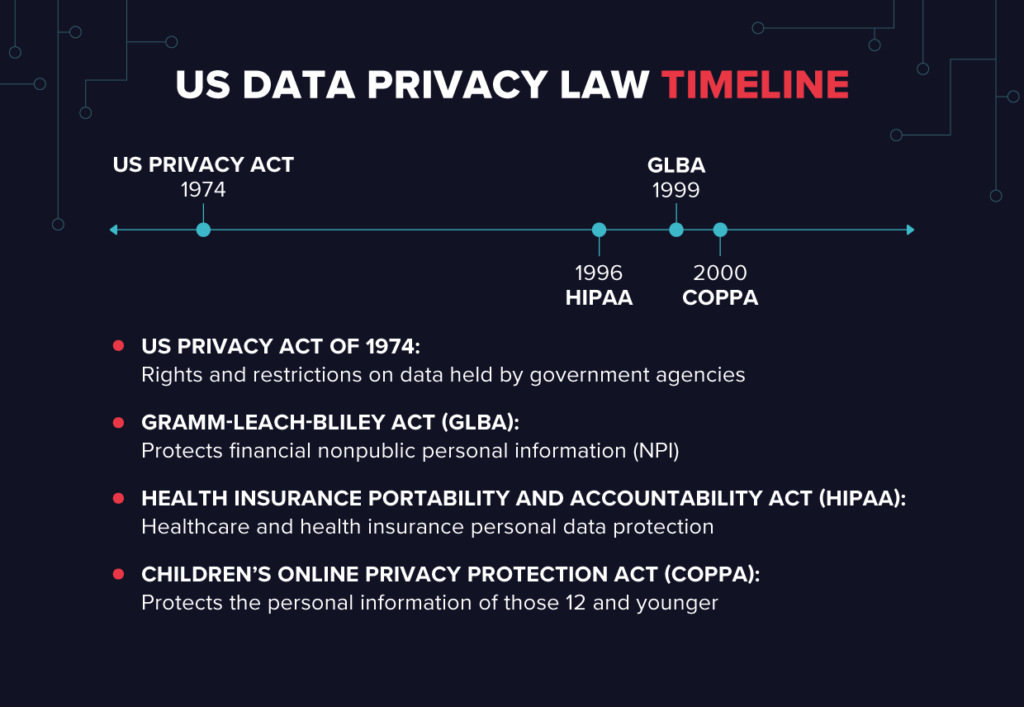

We do not have a central federal law in the USA, like the EU’s GDPR.

Instead, there are several vertically-focused federal laws and a generation of consumer-oriented laws coming from the states.

IOpenUSA secure privacy

US Privacy Act of 1974

In the last century, when databases were the height of computer technology, Congress and others were (rightly) concerned about the potential misuse

of personal data held by the government.

Congress passed the landmark US Privacy Act of 1974, which contained essential rights and restrictions on data held by US government agencies, and

should look very familiar to data pros.

I’ll list them here because they’re the first references that I know of for everything that followed:

- Right of US citizens to access any data held by government agencies. And a right to copy that data.

- Right of citizens to correct any information errors

- Agencies should follow data minimization principles when collecting data – the most minor information is “relevant and necessary” to accomplish its purposes.

- Access to data is restricted on a need-to-know basis – for example, for employees who need the records for their job roles.

- Information-sharing between other federal (and non-federal) agencies is restricted and only allowed under certain conditions.

HIPAA

Passed in 1996, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was landmark legislation to regulate health insurance.

It is a very complex law with lots of moving parts but included both data and security sections.

The data protection part of HIPAA is found in The Security Rule.

HIPAA also laid down data confidentiality requirements that can be found in, wait for it, The Privacy Rule.

If you’ve ever filled in a form at your doctor’s office allowing spouses and other family members to review or see your health information, what HIPAA

refers to as protected health information (PHI)

This Rule contains a convoluted list of rules on who gets to see PHI. But in short, a healthcare provider or “covered entity” more or less has permission

to use patient data related to “treatment, payment, and health care operations.”

However, using the data for marketing purposes or selling the PHI requires explicit authorization.

HIPAA’s minimum requirement is an excellent example of PbD principles applied to sharing of PHI.

It says that covered entities that share data for marketing purposes other than the ones mentioned above should limit who gets to see it.

Health organizations are supposed to evaluate their data and practices and put in place safeguards to limit “unnecessary or inappropriate” access to

PHI. In effect, role-based entry for PHI.

COPPA

Back in the early days of the early Internet, circa 2000, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) took a first step at regulating personal

information collected from minors.

The law prohibits online companies from explicitly asking for PII from children 12 and under unless there’s verifiable parental consent.

Updates to COPPA’s regulatory rules a few years ago effectively expanded the reach of the law.

They broadened the type of personal information to be protected, including screen names, email addresses, video chat names, photographs, audio

files, and street-level geo coordinates.

These updates also extend security coverage to third parties using children’s data.

The originating website operator must take “reasonable steps to release children’s personal information only to companies that are capable of

keeping it secure and confidential.”

GLBA

Another late 90s legislation, Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), is an enormous slab of banking and financial law that has buried essential data privacy

and security requirements in it.

Its personal information protections are a significant improvement over previous consumer financial data laws — see the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

Overall, Gramm- Leach-Bliley Act protects nonpublic personal information (NPI), which is defined as any “data collected about an individual in

connection with providing a financial product or service, unless that knowledge is otherwise publicly available,” essentially PII with an exception for

any widely available financial fact, for example, property records.

You may have noticed that banks periodically mail out data privacy notifications explaining the categories of NPI that are being collected and shared,

along with special opt-out instructions.

That’s due to GLBA’s somewhat limited privacy protections. Consumers can opt-out if they don’t wish that information to be sent to a “non-affiliated.”

Third-party.

However, for third-party companies affiliated with the bank or insurance company, part of the, cough, “corporate family” controls under GLBA to

restrict the sharing of the NPI. That’s quite a significant loophole, and GLBA is not a model for Internet-era privacy law.

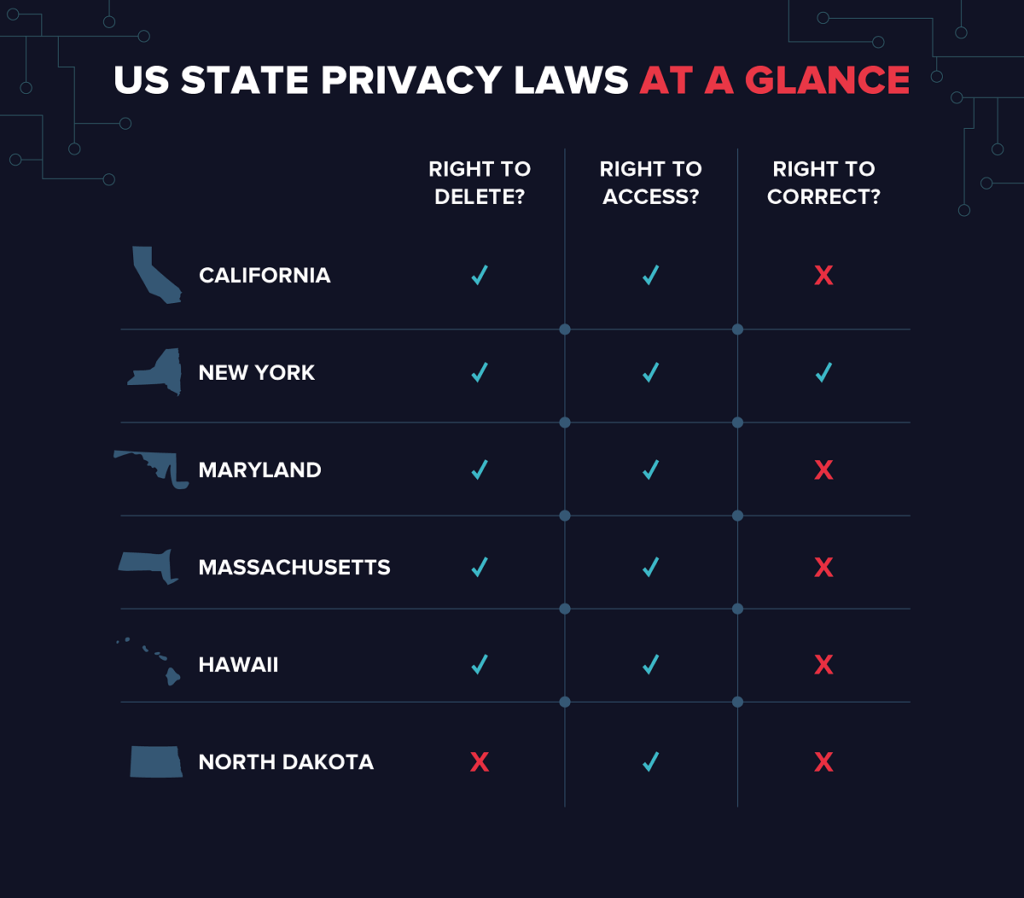

US State Data Privacy Laws

In the USA, we got several federal and consumer-oriented privacy laws from the states.

IOpenUSA paid surveys privacy 2

California Consumer Privacy Act

In 2018, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) was signed into law. Its goal is to extend consumer protections to the internet.

It’s not an exaggeration to say the CCPA is the most comprehensive internet-focused data legislation in the US, with no federal equivalent.

Under the CCPA, consumers have a right to access through a data subject access request (DSAR) the categories and specific pieces of personal

information held by covered businesses.

Businesses can’t sell consumers’ personal information without providing a web notice (“a clean and conspicuous link”) and allowing them to opt out.

Like the GDPR, there is also a “right to delete” with some exemptions for consumer personal information on request.

The CCPA also gives consumers a limited right of action to sue if they’re the victim of a data breach.

There’s a more general ability for the state Attorney General to sue on behalf of residents.

Legislation is in the works to broaden consumers’ private right of action to sue on other grounds.

Another striking innovation within the CCPA is its inclusive definition of personal information: “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is

capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.”

That covers a lot of ground and is similar to the GDPR’s expansive view of personal data.

To bring it back to the “black letter law,” the CCPA also contains a long list of identifiers it considers personal information, including biometrics,

geolocation, email, browsing history, employee data, and more.

The CCPA also introduces “probabilistic identifiers.”

Attorneys will debate what this means, but data with a greater than 50% chance of identifying someone will be treated like a deterministic

identifier.

Perhaps a combination of, say, Netflix viewing history and geolocation data may be enough to tip the scales.

By the way, other states have picked up the probabilistic term in their laws (below).

California goes “meta” with its probabilistic identifiers.

While the focus — and rightly so has been on extensive privacy rights for consumers, there’s also a data security component to the CCPA.

The law calls companies to “implement and maintain reasonable security procedures.”

What does that mean? No one’s sure, though there are strong hints that the California government is

looking to the Center of Internet Security’s top 20 controls and the NIST Critical Infrastructure Security (CIS) Framework as baselines.

With no federal answer to GDPR on the horizon, several other states are taking a page from California’s book by drafting their regulations to give

citizens increased control over their data.

While most of these bills use CCPA as a framework, there are differences.

We’ve even put together a cheat sheet at the end to compare the different proposed state laws.

Let’s first look at two tough proposals from New York and Massachusetts.

Massachusetts Data Privacy Law

The proposed Data Privacy Law (S-120) shares much of the CCPA language.

Consumer access to personal information?Â

Right to Delete?

Explicit notification of rights and a chance to opt out of third-party data sales?Â

A broad definition of personal information, including probabilistic identifiers?Â

There are a few essential divergences from the CCPA, including the right for consumers to sue for violating the proposed Massachusetts law.

Consumers “need not suffer a loss of money or property due to the violation” to bring an action.

Attorneys point out that Massachusetts companies have enormous potential exposure to class-action lawsuits: plaintiffs can recover up to $750 per

consumer.

For example, in 2017, almost 400,000 Mass. residents were affected by data breaches, leading to the possible exposure of nearly $300 million for that

year if the law had been in effect.

New York Privacy Act

New York’s proposed S5642 (currently on hold) contains some of the hallmarks of CCPA.

There’s a right to delete and request personal information. The definition of personal information, “any information related to an identified or

identifiable person,” includes a pervasive list of identifiers: biometrics, email addresses, network information, and more.

Unlike California and similar to Massachusetts, New York’s act has a private right of action for any violation of the law! And the law applies to all

businesses without any revenue threshold, which differs from California and other states. This makes the proposed NY law quite strict.

The NY bill only requires businesses to disclose to consumers the broad categories of information shared with third parties.

Under some circumstances, consumers would have the right to request copies of specific information shared.

Another key difference is that the proposed NY law imposes the role of data fiduciary”, forcing all NYS businesses to be legally responsible for their

consumer data.

The NY act takes a very expansive view: “exercise the duty of care, loyalty, and confidentiality expected of a fiduciary concerning securing the personal

data of a consumer against a privacy risk; and shall act in the consumer’s best interests, without regard to the interests of the entity, controller or data

broker”.

In short: consumers own the data.

The NY act also allows consumers to correct inaccurate information, making it closer to the EU GPDR. None of the other clones, including California,

go that far!

Hawaii Consumer Privacy Protection Act

Hawaii’s SB 418 is similar to the CCPA, offering the same significant rights and protections (potentially more, based on the bill’s current wording).

While CCPA explicitly applies to websites that conduct business in California, Hawaii’s SB 418 bill has no similar clause.

In theory, websites based anywhere worldwide could violate the law if they don’t offer adequate protection as outlined in the bill.

However, the bill will likely be amended later to focus solely on Hawaiian-based websites.

Maryland Online Consumer Protection Act

Maryland’s SB 613 is another bill with the potential to expand the scope of CCPA in some areas. However, businesses will have similar obligations to

disclose information usage to a lesser degree

than under CCPA.

And like California and Massachusetts, there’s also a “probabilistic identifier” to refer to a particular type of personal information. Go, Maryland!

However, this bill goes beyond the scope of the CCPA when disclosing third-party involvement. Under CCPA, companies must only disclose if

consumer information is sold to a third party.

Still, per Maryland’s SB 613, companies must disclose any information passed on to third parties, even if that data is transferred for free.

This bill also prohibits websites from knowingly disclosing any personal information collected about children.

North Dakota

North Dakota’s HB 1485, currently in the state’s House of Representatives, is the most lightweight bill on this list.

The only significant clause of HB 1485 would completely restrict websites from passing on any information to third parties without the consent of

users.

There is no right to have information removed or deleted once consent has been granted.

Source Complete Guide to Privacy Laws in the USÂ

How to Keep your Privacy Safe

The best way to protect your privacy is to avoid surveys scams

You need to recognize: that if there is something too good to be true, then it probably isn’t

There is nothing to be afraid of in any legitimate survey panel, and your information is safe and secure.

A lot of people are getting scammed these days.

But market research panels cannot harm you! In any case, where there’s nothing at stake, then why would anyone be so terrified?

It doesn’t make sense when the risk isn’t real, right?

So please do yourself a favor: don’t let fear guide decisions about what things seem risky enough before trying them out with no consequences.

Always remember safety comes first.

Conclusion

The key to keeping your information safe is recognizing and avoiding fake survey panels and offers.

There are federal and state laws that protect your privacy in the USA.

Never give your vital personal data like credit card numbers or social security numbers to any survey panel, even if it’s reliable.

We hope that the information we’ve provided has been helpful to you and that it will help keep your personal data safe.

If you like this blog post, please consider joining us or sharing it on social media with family and friends who may be interested in protecting their privacy as well!

References

GreenBook: Market Research Fraud: Distributed Survey Farms Exposed

Minnesota Attorney General: Avoid Survey Scams